Behind the Scenes: Chris Johnson and the Art of a Career in Biophysics

Chris Johnson started out at the MRC’s Centre for Protein Engineering Unit in 1992. The building for this MRC unit was directly connected to the LMB enabling collaboration with LMB staff and to access core facilities such as the workshops. Chris joined the LMB in 2009 as head of the newly created biophysics facilities that has continued to support scientific staff in all LMB divisions.

Here Chris reflects on his varied career, how science and his role has changed and what the future holds as he looks onwards to retirement.

Before the LMB: from fish vaccines to calorimetry and thermodynamics

I completed a degree in biology and my first job was at a university in Scotland, where they had an institute studying aquaculture – basically the science of fish farming. My project was developing vaccines against bacterial diseases of farmed salmonid fish. It combined bacteriology in the lab with field work and vaccine trials at commercial farms.

After working in this area for a few years I decided that I would need a PhD to advance my career. Since there was no funding for a PhD aquaculture, I took a radical change of direction and worked in the same university, but in the Department of Biochemistry on a PhD studying protein folding, trying to use limited proteolysis to probe structure formation during the folding process. This was in an era before routine molecular biology so there were no mutants, and material was purified from natural levels of expression. The protein folding problem was an exciting area in protein chemistry and even the rather primitive experiments of my PhD seemed to be giving some insights into how the primary amino acid sequence dictates the three dimensional fold.

After my PhD I took a post doc at the University of Glasgow studying the thermodynamics of protein stability and protein interactions. We used the technique of calorimetry as it gives direct access to the thermodynamics through measurement of the heats. However, at the beginning of the project there was no commercial equipment sensitive enough to measure these tiny energies and so some of my time was spent adapting and building calorimetric instrumentation. Eventually ultra-sensitive biocalorimeters became available that made the measurements somewhat more routine and with this approach I could begin to see the fundamental driving forces stabilising proteins and their interactions with other biomolecules.

This postdoc combined physics and chemistry with a bit of instrument development and so I seemed to have jumped quite a distance from my early work on fish biology.

Centre for Protein Engineering – the ‘calorimetry guy’

I took a position at an MRC Unit in Cambridge in 1992. Alan Fersht was the director of the Centre for Protein Engineering, and the unit was studying protein folding, structure and design. By this time, molecular biology was more routine allowing the effects of changes to the amino acid sequence on folding and structure to be determined.

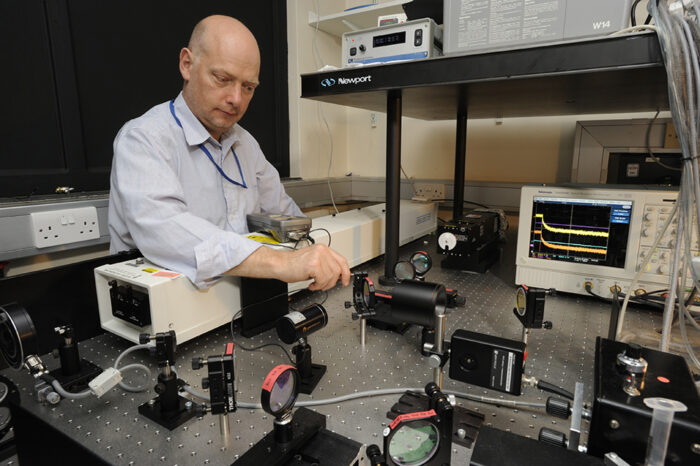

A core method in Alan’s approach was using Phi value analysis, where the effects of mutation on the kinetics of folding were studied allowing one to infer if specific interactions seen in a protein structure were formed or not in the transition state for folding. We used a variety of kinetic mixing methods such as stopped flow and continuous flow. Part of my work involved modifying and improving commercial instruments of this type or building them from scratch. There was always a race to study faster and faster folding events in smaller proteins that allowed overlap with the limited timescale of computational approaches available at the time. Therefore, we used non-mixing relaxation techniques such as temperature-jump to measure the kinetics down to sub-microsecond time scales. Again, these instruments were adapted or built in house with the help of the LMB mechanical and electronic workshops.

There was also a need for other more straight forward biophysical techniques such as calorimetry and spectroscopy in the CPE. I was in charge of keeping the instruments going and training people to use them properly. This sometimes extended to LMB scientists as the CPE had a much wider range of biophysical methods that were not available in the LMB. Thus, I became the local biophysics and ‘calorimetry guy’.

LMB – birth of the Biophysics Facility

Eventually the CPE closed, and I joined the LMB in 2009. The LMB had not had much biophysical instrumentation and what there was tended to be spread around the building. So, it made sense to combine the infrastructure of the CPE and the LMB into a new biophysics’ facility with me as the head. Initially I was based in the old CPE building, which was largely empty, but eventually, with the opening of the new LMB building in 2013, the facility was fully integrated into the mothership.

We recruited another member of staff and together we have built up a world class biophysics facility. New instrumentation and techniques have been developed, and we have been able to acquire these and incorporate them into the facility. We work across all divisions of the LMB supporting the 50+ groups of scientists and their many projects. This is quite a change from the more focused work of the CPE, and it is tough to keep on top of the background to the wide variety of projects that we get involved with.

One of the reasons for staying within the MRC at the CPE and LMB for a large part of my career was the attraction of a permanent position which allowed me the opportunity to modify, improve (or even build from scratch) instrumentation that allows measurements to be taken that could not be obtained otherwise. There is definitely something deeply satisfying in seeing a high-quality set of data or observing events in a time regime which was previously inaccessible. Just making measurements of the highest quality with minimal scatter of data values is rather rewarding even if the data are not of critical importance. I suppose this has parallels with any craftsman being proud of their work even if it is not immediately visible to others.

I do not have a formal engineering background other than the curiosity to take things apart and fix them, or just to see how they work. The LMB has exceptional workshop facilities, and this allows this curiosity to spill over into my scientific work. I am definitely happy to have had that opportunity and the chance to resolve some difficult problems using this approach.

The facility has contributed to many papers in high profile journals and where we have made measurements and analysed the data then this often results in co-authorship. I have also contributed review articles and edited a book so there is a significant paper trail from my time at the LMB.

A creative flare

At one point I wanted to improve my engineering credentials, so I enrolled on an evening class in welding. It was actually a course on welding and sculpture. The teacher was a welder who wanted to be an artist and during the course he insisted that we come up with an artistic object or image that we would create out of metal. He clearly wanted to see artistic inspiration and preliminary sketches in a notebook. On the day of the class I was panicking because I did not have anything to show and so I printed views of a small protein structure from all angles using a program RasMol and stuck them onto a cardboard box cube and took it along. I was rather worried about my lack of artistic preparation, but the teacher was very happy since he seemed to think that my work was spilling over into my creative side and my ‘art’. Actually, for me it felt like I had escaped doing my homework!

I made the model of the protein and then a few years later I put it into the annual LMB Arts and Crafts show where it was seen by other LMB scientists. A few years later one of these scientists contacted me asking if I would make a model of another bigger protein that his company was making so that he could have it on his board room table when he talked to investors. I made a number of these models for him and one of them ended up being given to Greg Winter. This model then appeared when Greg was being photographed after winning his Nobel Prize. It also served as inspiration when he had his portrait painted as master of Trinity College. It is rather odd to think that these welded models have ended up in such auspicious settings and now immortalised in the hall at Trinity College.

After LMB…

After working at the LMB for so long, I’m not sure how I feel about retirement yet – maybe I’ll come back as a postdoc! I don’t have any fixed plans for the moment, but I will probably increase the amount of volunteering I am doing to keep me busy. I will probably do more gardening, since that is what retired people do, and continue growing rare chilli plants and other exotic veg. Who knows, I may even try something genuinely art-related like portraiture…

Chris was interviewed for the 2024 LMB Alumni Newsletter on the 13th November