The third in our series of Group Leader profiles written by science writer and LMB alumna, Kathy Weston, is a profile of Mariann Bienz, a Group Leader in the LMB’s PNAC Division.

If one were asked to describe Mariann Bienz in one word, it would almost certainly be: determined. Her persistence and focus took her from a graduate student working on tRNA, through a postdoc on heat shock genes in frogs, to her long-term objective of studying gene expression in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. She’s since built a highly successful career using Drosophila and other model organisms as a way of unravelling how communication between cells is mediated, in the process being elected to the Royal Society and the Academy of Medical Sciences, and becoming Deputy Director of the LMB.

Mariann first heard about the concept of selector genes in Drosophila as an undergraduate in her native Zürich, and was fascinated by the idea that the expression of a particular group of genes could give rise to positional information able to dictate the body plan of an animal. However, there was a snag: none of the selector genes had been cloned, and the obvious route into the fly world, pure genetics, was one she had no great interest in taking. Instead, she decided to arm herself with the molecular biology skills she’d eventually be able to deploy in the fly by working on one of the hottest problems of the time; how tRNAs, the small RNA molecules that direct the building of new proteins at the ribosome, can in certain circumstances adapt their reading of the genetic code.

Mariann’s PhD on tRNA took her out of Zürich to an EMBO course, where she met LMB legend John D. Smith, who encouraged her to apply to the lab. Unfortunately, John was beginning to wind down his research, and Sydney Brenner (to whom she also applied) had lost interest in suppressor tRNAs by then. Instead, Mariann got herself a place with John Gurdon, whose lab was using oocytes from the frog Xenopus laevis as an assay system to look at gene expression.

Things didn’t go quite as expected. “I arrived in spring 1981, with the plan of staying for a year and then going back to Switzerland”, Mariann recalls. “I was completely uprooted – my English was rotten, I knew no-one in Cambridge, and I’d left all my friends and family behind.” However, the culture shock soon subsided. “Within half a year I was as happy as a fiddle!” she laughs. “I came from a lab where we were very limited technically, and when I got to the LMB, the sky was the limit. And I loved England!”

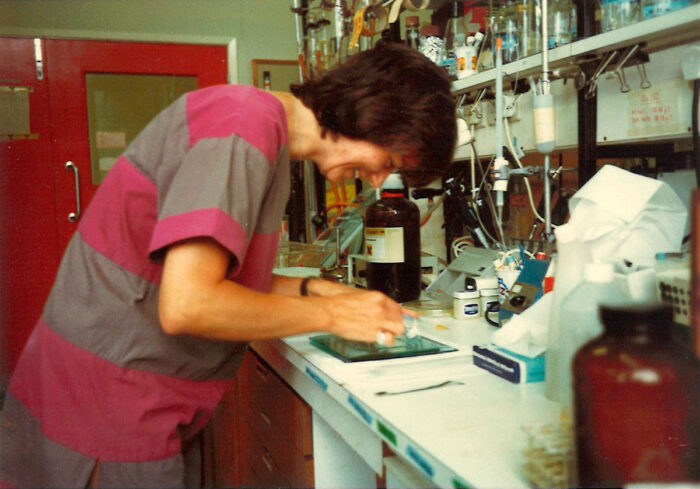

John Gurdon left the LMB the year after Mariann arrived, but she stayed on as an independent postdoc, as by then she’d started to clone frog heat-shock genes to study their oocyte-specific regulation. She also began to collaborate with a new young group leader, Hugh Pelham. In a romantic twist, this fruitful scientific partnership morphed into a more personal one, and the couple eventually went on to get married.

Towards the end of her postdoc, Mariann, and molecular biology, finally made it into flies. P-element transformation, a way of introducing foreign DNA into flies, was published in 1982, and the Drosophila selector gene, Ultrabithorax (Ubx), was cloned the following year. Mariann began working on how Ubx was regulated in response to positional information in fly embryos, and left the LMB in 1986 for an Assistant Professorship at the University of Zürich. She arrived into a science faculty comprising more than sixty men and only two other women, both single without families. “Every now and again, something baffling happened”, she says. “I got letters for my wife inviting her to come to the professors’ wives’ tea parties, and when I first got there, many people thought I was the secretary of Professor Bienz. It was quite something!”

Mariann’s work in Zürich secured her a reputation as one of the demystifiers of the complexities of Ubx expression, and also set her on track for the next stage of her career, looking at how signals from outside a cell control gene expression. In pioneering studies of the fly embryonic midgut, she showed that signals could pass from the outer mesodermal cell layer to the inner midgut epithelium, and that these signals could specify cell differentiation in the larval gut by turning on another selector gene, labial. Crucially, her lab then discovered that one of the signals playing a key role in this induction process came from an incredibly ancient cell communication pathway, the Wnt signalling pathway. Wnt signalling controls both embryonic development and, also, as it turned out later, adult stem cells in all animals. If activated incorrectly, it can cause cancer, most notably bowel cancer.

When she was recruited back to the LMB as a group leader in 1991, Mariann focussed on the molecular mechanisms that allow a Wnt signal at the cell surface to be transmitted to the cell nucleus. Working out the intricacies of this signalling pathway has taken Mariann on a deep dive into fundamental mechanisms of transcriptional regulation, and the biology of signalosomes, the molecular machines mediating signal transduction. It has also led to highly productive collaborations with researchers in fields as diverse as cancer and, most recently, plant signalling. For the former, Mariann’s lab has used flies as a genetic screening tool to identify potential new therapeutic targets in bowel cancer, as the downstream part of the Wnt pathway was thought to be undruggable. This led them to the discovery of a nuclear multi-protein complex termed the Wnt enhanceosome, which regulates a Wnt-dependent gene expression programme in the stem cell compartment of the mammalian gut, and which promotes intestinal tumorigenesis.

Looking at Mariann’s publication record, one might think that she’d been single-mindedly slogging away in the lab for her whole career, but the truth is rather different; in the early years when she was establishing her reputation, she had two babies, and has always been completely engaged with family life. “I loved the babies – that was my happiest time ever!” she says. “My career took a bit of a dip for a few years but I made up for it later on. At the LMB, you don’t have any teaching or grant writing, so that helps enormously, but I also didn’t travel or sit on committees until the kids were much older.”

Where does Mariann’s determination come from? Her upbringing, she says: “I know I have incredible focus and I always had that, even as a child. Also, I have three younger sisters for whom I was regularly responsible, so I was used to taking charge from an early age. My father was quietly confident in me and very supportive at crucial times, and he really appreciated that I went my own way and took up a professional career in science. But I also learnt from my mother what it takes to raise a happy family.”

Mariann takes her obligations as a senior woman in science very seriously. To help other established women climb higher on the career ladder, she makes a point of nominating women for election to the Royal Society and other professional bodies, and together with Daniela Rhodes, a long-time LMB group leader who is now based in Singapore, she promoted the first EMBO Women in Science meeting in 2001 and reported on its outcome back at LMB – the first-ever ‘women in science’ event at LMB. Her mentoring of younger women is informal, but no less useful, and she’s not afraid to tell them that having a scientific career can involve some hard choices: “You have to prioritise your scientific aspirations”, she says, “even if it sometimes means arranging the rest of your life around them.”

As the newly appointed LMB Deputy Director, Mariann wants to see the LMB moving towards becoming a more gender-balanced community at group leader level. “Historically, we’ve not been good at recruiting women, although I think once women are here, they really like the freedom and flexibility the LMB offers them to flourish as a scientist”, she says. “It’s a great place, but to keep it that way we need to make sure that we can attract the best people, irrespective of their gender.”