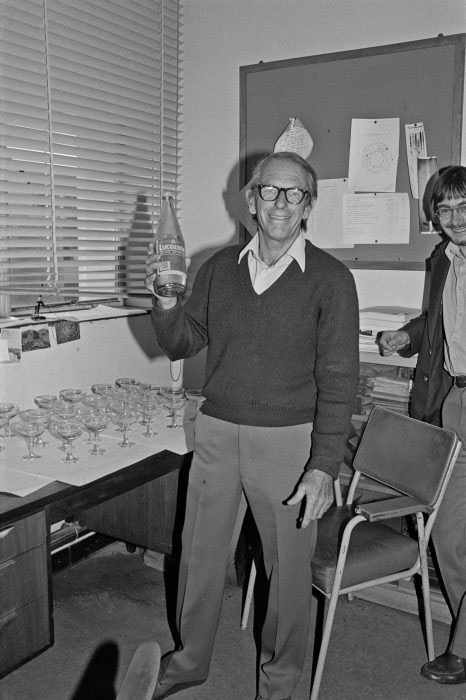

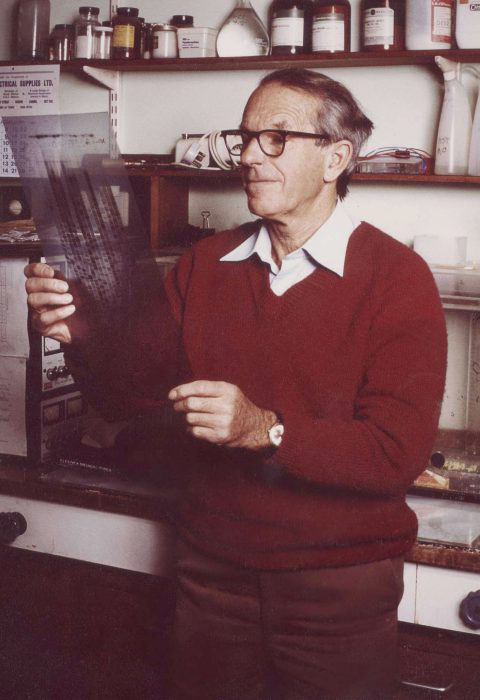

Fred Sanger at the LMB:

From DNA sequencing to the advent of genomics

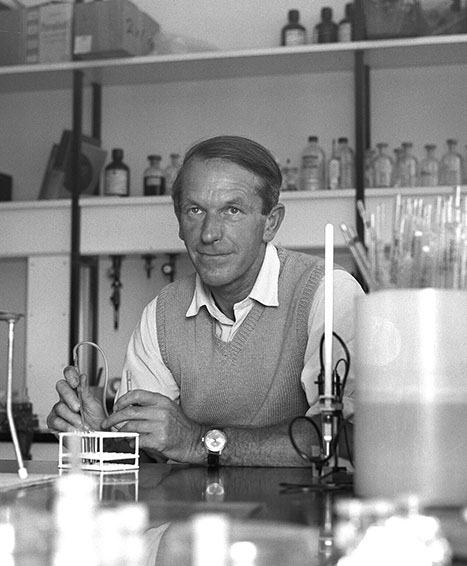

One modest, reserved man, working at the lab bench in a small laboratory in Cambridge, invented a technique that would be used worldwide and would forever change how problems in biology and medicine were viewed. That man was Fred Sanger, born over 100 years ago on 13th August 1918, and the technique he developed was dideoxy sequencing of DNA.

By the time Fred worked on the sequencing of DNA, he had already developed a method for sequencing proteins, in particular working out the chemical structure, or sequence, of insulin. This involved determining the order of amino acids, the base units that make up proteins. In 1958, Fred was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work.

“This award had an important and stimulating effect on my subsequent career. This recognition of my work gave me renewed confidence and enthusiasm to continue in this way of life, which I enjoyed.

Fred Sanger,

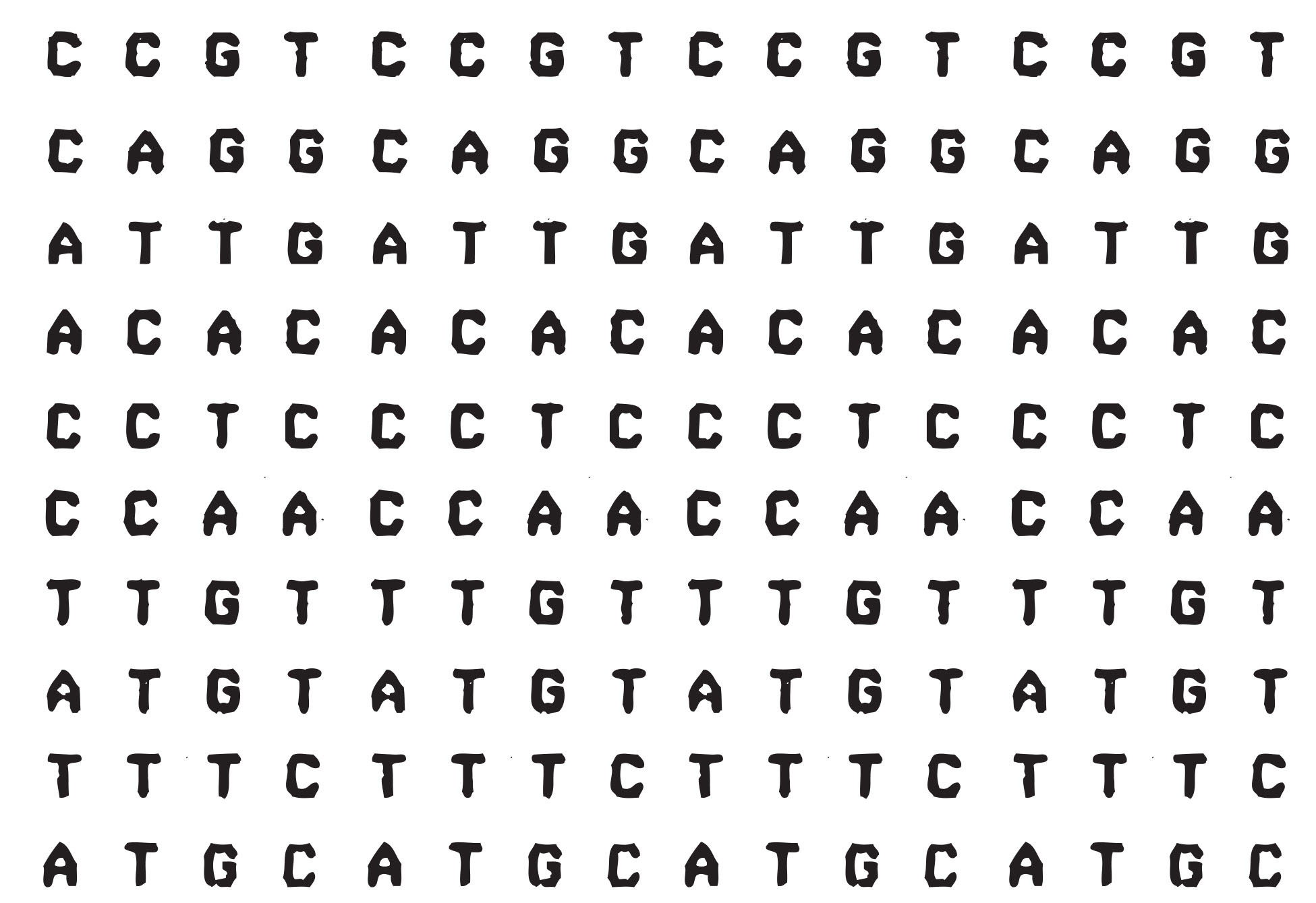

Les Prix Nobel, 1980.From the 1940’s, scientists started to think that the genetic material of life was DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid. A step to proving this was the deduction of the molecular structure of DNA by Francis Crick and James Watson, using X-ray diffraction patterns of DNA crystals by Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. In 1953 they unveiled the double helical structure of DNA, and revealed that the four organic bases, the nucleic acids – adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C) and guanine (G) – are paired in a specific manner between the two helices. However, what they couldn’t reveal was the order in which these bases appear – the chemical structure, or sequence, of DNA.

“There was a lot of pressure to get on to DNA, particularly from Crick. He was always around the lab talking to people about DNA. I found that very useful.“

Fred Sanger,

The Biochemist, 27, 31-39, 2005

In 1962, Fred, along with fellow MRC funded scientists, Max Perutz, Francis Crick, John Kendrew and Sydney Brenner, moved into the newly built MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB), on the outskirts of Cambridge. And Fred began to look at the problem of sequencing nucleic acids.

At this point very little was known about sequencing nucleic acids and there were two main problems to overcome: the only known nucleic acids were very large, and consisted of only four components – the four different bases. With the techniques available at the time a sequence with only four elements was much more difficult to solve than a sequence with 20 elements.

So why did Fred attempt this?

“Because of its intrinsic fascination and my conviction that a knowledge of sequences could contribute much to our understanding of living matter.”

Fred Sanger,

Les Prix Nobel, 1980.Using his prior experience from sequencing amino acids, Fred and colleagues set about trying out different methods for sequencing nucleic acids. After more than 10 years, the dideoxy sequencing technique, a brand new approach to sequencing, was developed. The method involved copying DNA while applying chain-terminating inhibitors, dideoxys, so that copying stops every time a particular base – A, C, G or T – is reached. The position of this base can then be plotted. Different dideoxys are used for each of the four bases, producing four samples which when run on acrylamide gels show the position of the bases. This produces the distinctive banded pattern – the DNA fingerprint.

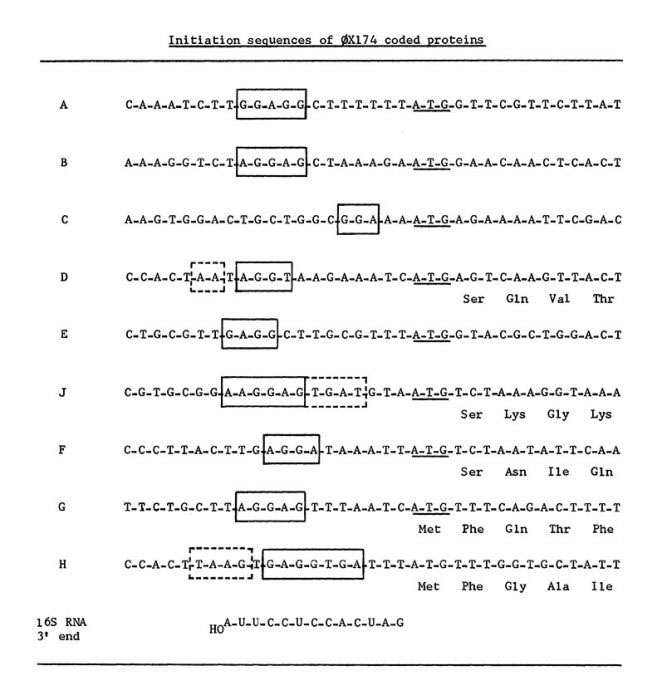

Through the work to develop this technique, a number of important milestones and discoveries were made. The specimen used for the work was phiX174 bacteriophage, a single-stranded DNA virus – it became the first fully sequenced genome, when Fred and his team published their paper in 1977. Fred’s work also showed, for the first time, three important aspects of genetics:

“Fred was the first to directly confirm the genetic code, the first to discover the unexpected phenomenon of ‘overlapping genes’ and the first to show that the genetic code could vary in different organisms.”

George Brownlee,

Fred Sanger double Nobel laureate: a biography, 2014.

For this work, Fred, in 1980, was awarded his second Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

He is one of only five people to have received two Nobel Prizes

The only British scientist to have received two Nobel Prizes

The first person to be awarded two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry

“To win a second Nobel prize is so remarkable an achievement that we are all lost in admiration.”

Margaret Thatcher,

Prime Minister, in a letter to Fred Sanger, 16 October 1980.

The dideoxy technique was developed further, so the method became quicker and more and more data was collected. Computational programs were designed at the LMB for organising and analysing the data, and the technique itself was suitably automated by others. This would become key to the worldwide success of the technique, and for the completion of the highly ambitious project to sequence the complete human genome: all three billion nucleotide base pairs. This gave scientists the chance to look at the genetic basis of diseases, such as cancer, and to predict susceptibility to such diseases. It also made the development of personalised medicine possible and enabled the study of genetic evolution and ecology, and much, much more.

Few people outside of the world of science have heard of Fred Sanger, but in this field he is one of the most influential scientists of the twentieth century: an inspiration, a pioneer and the ‘father of genomics’.

“Fred Sanger was a modest, reserved man but to his colleagues and friends he always had a vision. He was a pioneer and a leader.”

– George Brownlee. Biogr. Mems. Fell. R. Soc. 61, 437-466, 2015.

“Sanger was happiest at the laboratory bench, where he worked tirelessly and single-mindedly. He performed elegant experiments with simple apparatus to solve extremely difficult problems. In so doing, he inspired younger scientists and attracted some of the best biologists in the world to Cambridge.”

– John Walker, Nature, 505: 27, 2014.

Fred, himself, explained what being a scientist meant to him:

“I believe that we have been doing this not primarily to achieve riches or even honour, but rather because we were interested in the work, enjoyed doing it and felt very strongly that it was worthwhile … Scientific research is one of the most exciting and rewarding of occupations. It is like a voyage of discovery into unknown lands, seeking not for new territory but for new knowledge. It should appeal to those with a good sense of adventure.”

Fred Sanger,

Nobel Banquet Speech, 1980.