How one molecule directs the immune response towards wound healing or bacterial defence and how this system becomes unbalanced in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a severe chronic disorder that is increasing in incidence worldwide. To identify new treatments, scientists need a better understanding of the role played by different parts of the immune system in this disease. Menna Clatworthy’s group, in the University of Cambridge Molecular Immunity Unit, which is housed within the LMB, has now identified a key signalling molecule in determining the balance between wound healing and defence against bacterial invasion.

The human gut is home to trillions of microbes. The immune cells that occupy the wall of the intestine need to react appropriately to different groups of bacteria: tolerating the “good bacteria” known as commensals and attacking invading pathogenic bacteria. If the immune system ignores the wrong bacteria, then infection can occur, while overreaction can lead to inflammation and IBD.

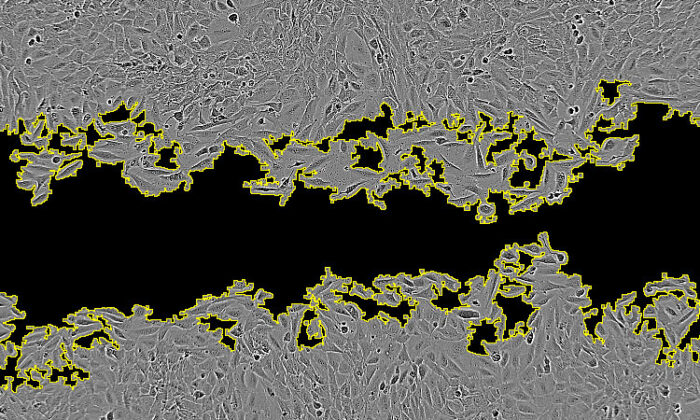

Macrophages are immune cells that are found in the intestine and, although named for their ability to engulf and digest cellular debris, microbes, and other foreign substances, they also have important inflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles. Tomas Castro-Dopico, a researcher in Menna’s group, studied gut biopsies from patients with IBD, as well as lab models of IBD, to study the signalling molecules (known as cytokines) sent between immune cells to amplify or suppress inflammation in the gut.

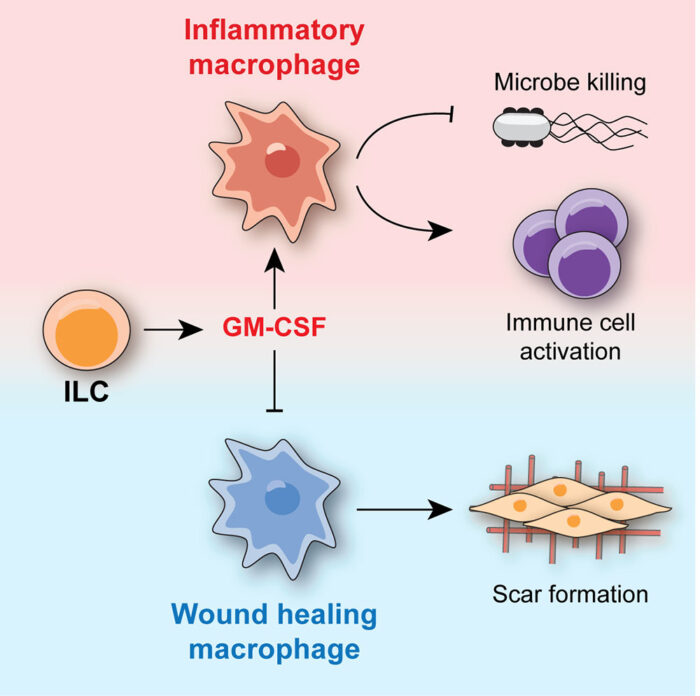

Tom, other members of Menna’s group, and collaborators at the Cambridge Institute of Therapeutic Immunology and Infectious Disease and the Wellcome Sanger Institute, identified a major cytokine that calibrates wound healing and bacterial defence functions of macrophages in the intestine, GM-CSF (granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor). They also identified the main cellular source of GM-CSF: innate lymphoid cells. The team found that lower amounts of GM-CSF promoted wound healing by macrophages, while higher levels increased inflammation, inhibited wound healing, and made macrophages that are better at dealing with gut-invading bacteria.

However, GM-CSF has a “Goldilocks effect” as too little GM-CSF can leave the gut susceptible to infection and excess wound healing could result in scarring and narrowing of the intestine, while too much GM-CSF can lead to an excessive immune response and cause collateral damage, so a fine balance is required.

While treatments for IBD have improved in the last two decades, a significant proportion of patients do not respond to treatments. GM-CSF has been investigated as both a target for neutralisation and as a potential therapy itself for IBD patients. This work demonstrates how neutralisation of GM-CSF may be useful in IBD patients with active flares of inflammation and also how it could be damaging by causing intestinal scarring in chronic IBD. IBD is a chronic relapsing condition, so different treatments might be needed depending on whether the system has become unbalanced towards excessive healing or excessive inflammation. An improved understanding of the immune system in the gut and how to rebalance the inflammatory/wound-healing response will allow development of new therapies.

The work was funded by UKRI MRC, University of Cambridge/Wellcome Trust Infection, Immunity, and Inflammation Programme PhD fellowships, China Scholarship Council, NIHR, Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, and Versus Arthritis.

Further references

GM-CSF calibrates macrophage defence and wound healing programmes during intestinal infection and inflammation. Castro-Dopico, T., Fleming, A., Dennison, TW., Ferdinand, JR., Harcourt, K., Stewart, BJ., Cader, Z., Tuong, ZK., Jing, C., Lok, LSC., Mathews, RJ., Portet, A., Kaser, A., Clare, S., Clatworthy, MR. Cell Reports 32, 107857

Menna’s group page

Arthur Kaser’s group page