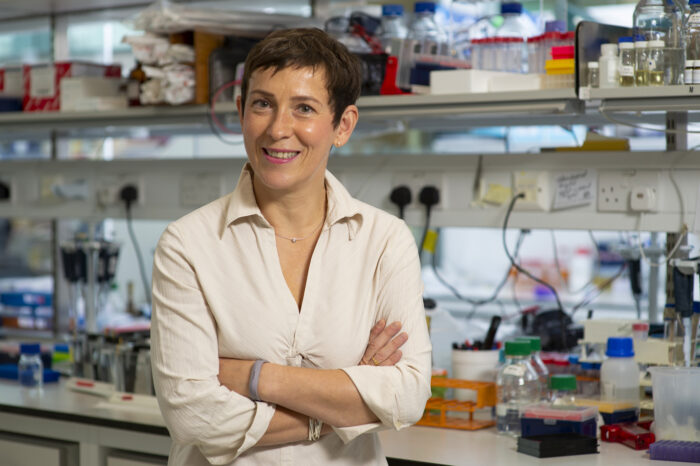

From the scientist’s view: a conversation with … Anne Bertolotti

Anne Bertolotti is an LMB Group Leader and Joint Head of the Neurobiology Division.

Anne did a PhD studying transcription alongside Laszlo Tora and Pierre Chambon at the Institute of Genetics and Molecular and Cellular Biology (IGBMC) in Strasbourg. Following this, she moved to the Skirball Institute, New York to work with David Ron. This is where she first began her work on misfolded proteins and the cellular response to such proteins. After further research at INSERM and Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, Anne joined the LMB as a Group Leader in 2006.

Anne’s group investigates the molecular basis of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases. These diseases share a common molecular origin; the deposition of proteins in abnormal conformation. Anne’s research seeks to better understand the mechanisms which underlie the deposition of these proteins and elucidate ways to prevent this. Chiefly, Anne and her group are pursuing methods to boost cellular defence mechanisms to find ways they could be exploited as therapeutic strategies against these diseases.

We recently interviewed Anne about her research, her career so far, and why she prioritises fun and fearlessness in her approach to science.

What is your earliest memory of science or scientific discovery?

My earliest memory of science would be the observation of a snowflake under a toy microscope as a child. Of course, as soon as the snowflake would hit the slide it would melt. So, I had to first cool down the microscope on the windowsill, and then I could observe the snowflakes and it was truly magnificent.

What is the most exciting thing about your research?

I think what’s remarkable about scientific careers is that every day pretty much, or every week, every month, there’s something really exciting coming up. It’s truly addictive actually. A lot of it is unpredictable, unanticipated. It’s very hard to think about other work or other professions that could bring the level of excitement that science does. We are the first to see the things we see. We are the first to uncover molecular mechanisms that are important for cells and organisms. And that’s why I’m a scientist.

Has there been an experiment or piece of work that didn’t go to plan, but turned out to have a positive, if unexpected, outcome? What did you learn from it?

Oh, this is a really fun question! Has there been an experiment that didn’t turn out as planned and led to an unpredicted outcome? There are many, and this is something we try to think about when we design an experiment. Not to just design the experiment to lead to the answer that we are all sort of looking for, but design experiments to reveal something important, including things that we cannot anticipate. I’ve been sort of spreading the idea of what I call the killer experiment, which is an experiment that is designed to kill the hypothesis that underlies the question we want to ask. And if the killer experiment doesn’t kill the idea, then it usually reveals something interesting that we want to follow up on.

Do you have a ‘scientific hero’, someone who has been a big inspiration on your scientific career?

I don’t have one. I think heroes are characters of comic books or novels, in my opinion. This isn’t to say that I have not been inspired by giants in science. I’ve been inspired by many scientists in many ways. I can cite a couple of papers that have impressed me, I can cite scientists that have given very remarkable talks, and so on. But I don’t have one scientific hero. I think maybe the idea here is, for me, science is not led by heroes, but by human beings. And we all have flaws. No one is perfect. We all make mistakes and often. When reporting on scientific careers, we always put the highlight on the successes, but often the successes don’t come in a linear manner. There’s a lot of hurdles and obstacles and bumps on the road. It’s an important point, science is led by human beings and not by heroes, in my opinion.

What skills do you think you need to be a good scientist?

The skills for good scientist – I’ve been thinking a lot about that, in recruitment or when I give mentoring sessions and talks at conferences or such. To me, I can name many, many qualities that one needs, but number one is perhaps fearlessness. Being fearless to explore the unexplored, to venture in areas when one knows nothing, when nobody has done anything before, is what drives significant discoveries. People need to be uninhibited and be able to try new experiments without the fear of failure. The fear of failure is often what restricts people in progressing in science, perhaps in life too, but we may not go there today.

How does your research benefit society as a whole?

It wasn’t by design, but it turns out that the work I’ve done as a PhD student and as a postdoc (so my early career), is now in in textbooks and that’s something that, at first, I was fascinated by. Recruiting somebody from Japan and saying, “Look, this is my Japanese textbook, and here is your name,” was a lot of fun. Contributing knowledge is important. And the idea that the discoveries we make in the lab, go to university in a short period of time through textbooks and such is very exciting. I really get excited when I’m invited to student symposia, for example.

And of course, there’s the idea throughout my career that by studying fundamental biological processes, inevitably the knowledge we will gain one way or the other will benefit human health. There is some of our work which has direct relevance to the clinic. A discovery we made in the lab that we published in 2011, a small molecule that protected cells from protein misfolding in cells, has been tested in humans and has shown benefit in a phase 2 clinical trial in ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). There were 18 individuals with a form of ALS that causes what is called bulbar onset for which the disease did not progress for the six months of the clinical trial. And that’s immensely rewarding – from the bench to tangible benefit in human. Of course, it’s a small number of individuals. I’m looking forward to seeing whether this can extend to larger clinical groups. For me as a scientist, generating knowledge relevant to improving human health and perhaps seeing how this can be used to produce tangible benefit in a human is tremendously exciting.

Is there a part of your job that might surprise people?

The people who know me a little bit won’t be surprised to hear that part of me being a scientist is having fun. I have tremendous fun in the lab. There’s a playfulness aspect to the work we do, the idea of creating experiments. Nobody has done this work before. Of course, some things fail and sometimes we realise after, “How did we not think about that?” That’s fun. Those who don’t know me may be surprised to hear that part of scientific careers, as far as I’m concerned, involves fun. The lab is a playground. I work with really talented, young people, and part of the fun is recruiting fun people to join the team and expand on our playground.

Has your scientific career been different from what you imagined? If so, how?

I have, I think, a great imagination but the one thing I did not imagine is my scientific career. Because it wasn’t planned at all. It happened one step at a time, one day at a time going forward. And perhaps I might link this to the one and only advice I got from Pierre Chambon with whom I did my PhD, “focus on the science and forget about the rest”. The context of this advice was after my PhD, the job market was pretty dull in France and we must have had a conversation about career advice and postdocs, and he said, “Just focus on the science.” I thought this is pretty cool actually. Just makes the thinking process far simpler because scientifically, I always kind of knew what I wanted to do. And if I didn’t know what I would be doing next year, I know that I will figure that out going forward. So, no long-term strategic planning, just one step at a time.

Anne was interviewed for the LMB Alumni Newsletter on 18th November 2022