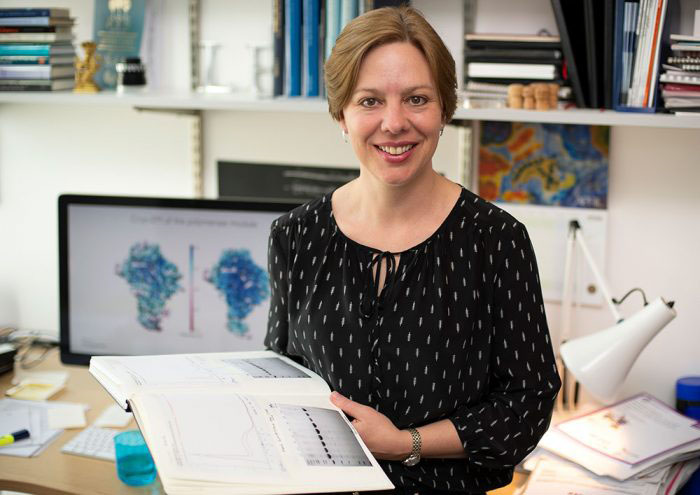

Lori Passmore: polyA tails and parenthood

In an age where scientific research is increasingly framed and measured by its translational potential, Lori Passmore is something of a heretic: she wants to characterise the molecular machines that regulate mRNA polyA tail formation simply because she’s curious how the process works. And in a further challenge, she knows the project is going to take a long time – her lab has been running for ten years and she’s not even close to being done. It’s fortunate that she works at the LMB, where long-term investment into curiosity-driven research is not only supported, but encouraged.

Of course, such research has to be on a worthwhile subject, and polyA tail formation is certainly that. Eukaryotic cells add polyA tails to almost every mRNA they make, and they’re absolutely essential for an mRNA’s stability and translation into protein. Given that without polyA tails, there’d be no multicellular life, it’s perhaps surprising that more isn’t known about how the tails are added and removed, but the process is something of a Cinderella, overshadowed by the idiosyncracies of transcriptional initiation, and the complexities of translation.

The multiprotein complexes that add and remove the polyA tails aren’t very well characterised, and they’re hard to work with because they’re large, and not particularly abundant in cells. After purifying the protein subunits and reconstituting them in vitro, Lori’s lab determines their structures using cryo-EM with computational methods to work out their 3D structures. Once structures are established, it’s possible to work out the function of the individual subunits, and to start to learn how the whole process is regulated. Recent successes include a high-resolution structure of the polymerase module that actually adds the polyA tail, and reconstitution of the nuclease responsible for defining where the mRNA is cleaved prior to polyA tail addition. “It’s been fun working with the fantastic people in my group who have done really amazing research”, says Lori. “Everyone has had a great paper out of the lab. Even though the projects are challenging, we have made lots of progress along the way.”

Running such a big project works very well at the LMB, even though Lori’s lab is quite small. She has no technical staff, but this is more than remedied by the range of expert research services on offer. However, protein purification is the responsibility of the lab, and can be very challenging. It’s sometimes necessary to work very long days, although Lori says that the lab works very well as a team, splitting days and working together collaboratively. After these mammoth efforts, she encourages people to take time off to compensate. “Working as a team is something I learned as a postdoc and established in my own lab when I started out. It’s now part of the lab culture”, Lori says. “You have to find the right balance or it’s easy to overwork”.

Lori and her now husband moved from Canada in the 1990s to do PhDs at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, and both went on from there to postdoc positions in Cambridge, with Lori working on ribosome structure with Venki Ramakrishnan at the LMB. For her PhD, Lori worked with David Barford, now also at the LMB, on the anaphase-promoting complex (APC). “APC was really fun as the field was brand new, and there were so many questions you could address biochemically”, says Lori, “and then for my postdoc with Venki, the structures were difficult, but a lot more was known”. It seemed a good plan when Lori started her own lab to blend the things she liked best about her PhD and postdoc: “I wanted to go back to not knowing so much about the system, but still work on gene expression control – one of the fundamental basics of biology”, she says.

The LMB was still in its old building when Lori started with Venki, so she experienced first-hand the famous canteen, where you were as likely to sit next to a Nobel Laureate as a fellow postdoc. “When you went up there it was always full and you just had to sit in one of the seats that were left”, she remembers, “you were forced to interact with lots of other people and although it was intimidating at times, you talked about your work from different angles, and it made you think more about what you were doing. I loved it, eventually!”

During their postdocs, Lori and her husband had their first baby, with the second born shortly after she started her lab. For both, Lori took six months of maternity leave, although she kept in touch with the lab throughout. “I wrote research proposals the first time round”, she says, “but I had a good sleeper so I was lucky!”. For her second child, the other group leaders stepped in and helped look after her lab members, so Lori didn’t have to worry that the lab was suffering. Being able to talk to some of the other senior women such as Mariann Bienz and Daniela Rhodes, who’d both had children at a similar stage in their careers, was very helpful: “They gave me some good advice, and I never felt that it was wrong to have children, or that I was being pressured into coming back to work”, she says. “I felt supported, but I was surprised by how many young women doubted that it was possible to have a family and a successful lab. They were already worrying they wouldn’t be able to do it, and that hadn’t occurred to me at that stage”.

Lori says her husband Mathew Garnett, who works at the Sanger Institute, has been a huge support from the start. They’ve tried to make their life as easy as possible, hiring someone to clean and garden, and they live a five-minute bike-ride from the LMB, so that Lori can get home quickly if there are any problems. “If something unexpected happens we just negotiate that”, she says, “and we make constant readjustments to keep things balanced.” The general policy is one of complete openness: “I tell my children if there’s something stressful at work, or why I sometimes need to work late, and I tell my lab if there’s something going on at home,” Lori says. “If I leave at three to pick up my children from school my lab knows, and they respect that. You don’t feel guilty if you’re open about what you’re doing. And it’s important to let the lab see that that’s normal.”

Juggling a busy life means Lori has to ruthlessly prioritise.”You have to be confident to say no or you just get run off your feet”, she says. “If I get an invitation I can’t accept I refuse it immediately so it doesn’t weigh on my mind.” Without a family support network in this country, she and Mathew have to plan their absences carefully too. “I print out a whole year calendar and block out when we’re travelling and when the school holidays are – I never travel in the school holidays”, Lori says, “and any travel is always a negotiation with Mathew.””

I’ve made the choices I wanted to shape my career and my personal life”, Lori says. “Having a family means I have to prioritise and try to find the right balance. I want to do things like go to my children’s concerts and pick them up from school once a week. And science is such a flexible job – I can easily leave the lab for my daughter’s concert at 2pm and be back by 3:30!” However, she’s aware that unconscious bias may have played a part: “There may have been times when I’ve been held back. It is clear that there are differences between how men and women are treated”, she says, “but I try not to dwell on this or it would eat me up. Things are changing but I would like to see this happen faster.”

Lori has always been quite self-confident, she thinks, but she isn’t sure how this came about. “I was a very busy child and loved to do loads of things, so I guess I just got used to putting myself out there”, she offers. “And actually, I’m not always confident, just very determined!” Asked if she has any advice on dealing with confidence, she points out that everyone gets worried about doing certain things, and that it’s more important to realise that if you don’t do the things that scare you, it may be detrimental to your career. “It is key to recognise that stress and uncertainty are a fact of life. Sometimes you feel nervous but you just have to push beyond that”, she says.

It also helps to talk about your worries. “We all have internal battles and feel more or less confident depending on what’s going on, but the important thing is to have sympathetic colleagues to discuss issues with, to help you think through problems”, she says. “I have an informal network of colleagues who I chat to, and I like to think that students and postdocs know that my door is open.”

“I have goals and plans but it is necessary to constantly readjust these, depending on where life takes me,” Lori concludes. “Life is busy, so you just fit it all in, do your best, and be proud of what you’ve achieved.”

Lori was interviewed for this article by Kathy Weston, February 2019