Antibody-secreting cells selected to recognise gut microbes form an immunological shield in the meninges lining the brain

The importance of our brain in controlling most other body systems and enabling reasoning, intelligence and emotion is reflected in the preventative measures humans have evolved to protect the brain. For physical protection, the brain is wrapped in three layers of water-tight tissue called the meninges and sits inside a solid bony case, the skull. However, defence of the brain from microbial invasion and infection has been less well understood. Menna Clatworthy’s group has now identified that immune cells derived from the gut defend the meninges.

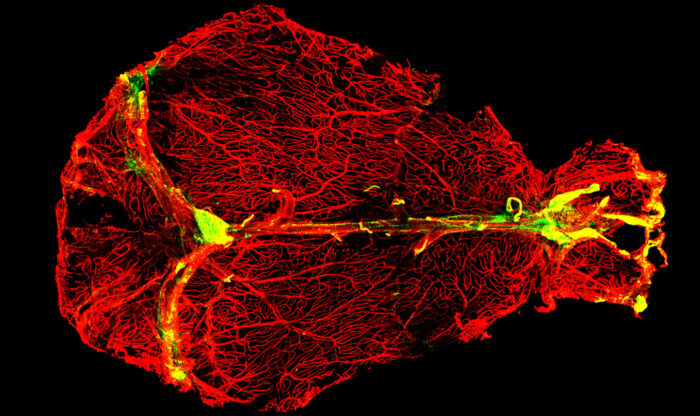

Zach Fitzpatrick, an NIH-OxCam PhD scholar working with Dorian McGavern’s group at NIH and in Menna Clatworthy’s group, in the University of Cambridge Molecular Immunity Unit, which is housed within the LMB, found plasma cells, a type of immune cell, positioned next to large blood vessels running through the meninges. Plasma cells secrete the antibodies used by the immune system to directly neutralise foreign substances and pathogens or label them for other immune cells to destroy.

There are multiple types of antibodies used by the immune system with different classes serving different functions and being primarily found in different tissues. Surprisingly, Zach found that the plasma cells in the meninges secreted IgA antibodies, which are most commonly found in the intestine, rather than IgG, the more common type seen in blood.

Indeed, Zach and colleagues found that the IgA-producing plasma cells in the meninges originated in the gut and observed that mice bred in completely sterile conditions without any bacteria in their gut did not have IgA-producing immune cells in their meninges. If bacteria were added back to the diet of these mice, IgA-secreting plasma cells were once again seen in the meninges.

Conversely, the team found that specifically removing these plasma cells allowed invasion of microbes from the bloodstream into the brain in mice, demonstrating the importance of the IgA antibodies for immune defence of the brain. Importantly, the team were able to confirm the presence of IgA cells in human meninges as well.

The fact that meningeal IgA antibodies are educated in the gut makes sense, because even a transient breakdown in the intestinal barrier allows microbes from the intestines to enter the bloodstream, making them the most likely invaders into the brain from the blood. As infection in the brain can lead to devastating consequences, seeding the meninges with antibody-producing cells selected to recognise gut microbes ensures a good immunological shield.

This work describes a previously unknown immune defence system protecting the brain that originates in the gut. This suggests that diet and antibiotic intake could alter this barrier. Importantly, this finding could help the design of strategies, including vaccines, that aim to specifically prevent encephalitis and meningitis by enhancing this antibody shield.

The work was funded by UKRI MRC, NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit, Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, Versus Arthritis, the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Further references

Gut-educated IgA plasma cells defend the meningeal venous sinuses. Fitzpatrick, Z., Frazer, G., Ferro, A., Clare, S., Bouladoux, N., Ferdinand, J., Tuong, ZK., Negro-Demontel, ML., Kumar, N., Suchanek, O., Tajsic, T., Harcourt, K., Scott, K., Bashford-Rogers, R., Helmy, A., Reich, DS., Belkaid, Y., Lawley, TD., McGavern, DB., Clatworthy, MR. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2886-4

Menna’s group page

Dorian McGavern’s page