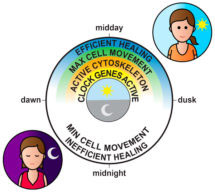

Internal body clocks, which time the length of a day in almost all organisms, control many aspects of human physiology and activity, from when we go to bed to when we perform best mentally and physically. Most importantly, these biological circadian clocks are in every single individual cell of our bodies, not just in the brain. A new study has shown for the first time that these clocks also have a role to play in the healing of wounds, by ensuring that skin cells move quickly to the damaged area.

The new research, led by John O’Neill’s group in the LMB’s Cell Biology Division in collaboration with NHS colleagues Ken Dunn from the Manchester Burns and Plastic Surgery Service and John Blaikley from the Centre for Respiratory Medicine and Allergy in Manchester, found that wound healing in humans is under the control of the biological circadian clock in skin cells, such that wounds incurred at night take 60% longer to heal than those acquired during the day.

One of the major roles of a skin cell is to respond to and heal wounds, such as cuts and scratches. Skin cells do this by moving into the damaged area, where they produce restorative proteins such as collagen. The ability of cells to migrate into wounds depends on an essential protein called actin. Research led by Nathaniel Hoyle in John’s group showed that the circadian clock ensures that actin in human skin cells is more active during the daytime than at night. Therefore, at night skin cells move more slowly into wounds, which take longer to heal. This is reversed in nocturnal mice, where skin cells move more quickly and wounds heal faster when injuries occur during the night: the time when mice are the most active.

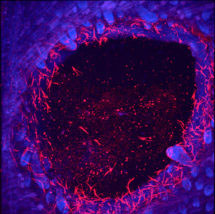

Using skin cells grown in a petri dish, as well as in living skin, wounds were produced at different times of day and the researchers observed how quickly skin cells move into the damaged area. This led to the prediction that people who are wounded at night will take longer to heal than those where the wound occurs during the day. With the assistance of NHS colleagues in Manchester, who monitor the outcomes of human burns victims, the team were able to confirm their prediction. Further studies of the microscopic structure of the skin cells involved showed how circadian changes in the internal structure of the cell controls how quickly a cell can heal a wound.

The efficient repair of our skin is crucial to preventing infection. When healing goes wrong we can suffer from excessive scarring or chronic wounds which never properly heal. It might be that cases where wounds do not heal properly are linked to problems with the circadian clock. Understanding more about how body clocks influence our ability to heal might inform clinical decisions, such as the best time to perform surgery.

The work was funded by the MRC, the Wellcome Trust and Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

Further References:

Paper in Science Translational Medicine

John’s group page

Mr Kenneth Dunn’s web page

John Blaikley’s research page

MRC Press Release