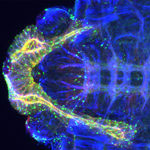

A collaborative team from LMB’s Cell Biology and Structural Studies Divisions has visualized the mammalian protein synthesis and export machinery at near-atomic resolution. The new research helps explain how secreted proteins, such as hormones, can cross an otherwise impermeable membrane to exit the cell.

It has long been appreciated that cells communicate with each other via proteins that are either secreted or embedded in the cell’s surface.