Therapeutic antibodies and the LMB

The discovery of antibodies more than 100 years ago, prompted scientists to develop a number of animal and human antisera to neutralise toxins and to treat viral and bacterial infections.

However, the development of antibodies to treat cancer and auto-immune disease presents major problems. Scientists not only needed to identify and isolate the disease target (which is typically a minor component in a complex mixture of human proteins) but they also needed to raise a human immune response against the disease targets. It is a particular problem to make human antibodies against human disease targets due to immunological tolerance.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

In 1975 the LMB’s George Köhler and César Milstein discovered a method to isolate and reproduce individual, or monoclonal, antibodies from among the multitude of different antibody proteins that the immune system makes to seek and destroy foreign invaders attacking the body. Köhler and Milstein won the 1984 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in recognition of this ground-breaking work.

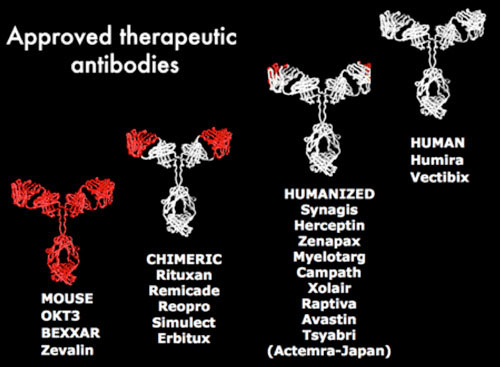

Monoclonal antibodies were initially developed from mice as a tool for studying the immune system. The method allowed the production of large amounts of highly specific antibodies, enabling reproducible research measurements and results. The early applications of monoclonal antibodies included grouping blood types, identifying viruses, purifying drugs and testing for pregnancy, cancers, blood clots and heart disease. However, applications in human medicine were limited because mouse monoclonal antibodies are rapidly inactivated by the human immune response, which prevents them from providing long-term benefits.

In 2010 Ana Fraile produced a film about Cesar Milstein and the development of monoclonal antibodies. This historical video can be found here.

Humanisation – the breakthrough

Monoclonal antibodies began to reveal their full therapeutic potential in 1986, when the LMB’s Greg Winter pioneered a technique to ‘humanise’ mouse monoclonal antibodies. This made them better suited to human medical use as they proved less likely to provoke an immune response in patients. The technique was used in the development of Campath by LMB and Cambridge University scientists; this antibody now looks promising for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. The technology has since been licensed to around 50 companies, which have each paid a one-off licence fee and agreed to pay royalties on any resulting drugs that reach the market.

Human antibodies

Further patented research by Greg Winter led to development of methods for making fully human antibodies. This involved making libraries of human antibodies for display on bacterial viruses. The technique was used in the development of Humira® by Cambridge Antibody Technology, an MRC spin-out company. Humira®, the first fully human monoclonal antibody drug, was launched in 2003 as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis.

LMB’s Michael Neuberger developed an alternative method for making human antibodies, using transgenic mice with human antibody genes. This has also led to several new human therapeutic antibodies.

New drugs for a range of diseases

Today, monoclonal antibodies account for a third of all new treatments. These include therapeutic products for breast cancer, leukaemia, asthma, arthritis, psoriasis and transplant rejection, and dozens more that are in late-stage clinical trials.

In 2021/22, an exhibition ‘From bench to blockbuster: the story of Humira – best-selling drug in the world‘ was held in the LMB Exhibition Room.